Monasticism played a decisive part in the religious life of Byzantium, as it has done in that of all Orthodox countries. It has been rightly said that ‘the best way to penetrate Orthodox spirituality is to enter it through monasticism’. ‘There is a great richness of forms of the spiritual life to be found within the bounds of Orthodoxy, but monasticism remains the most classic of all.” The monastic life first emerged as a definite institution in Egypt and Syria during the fourth century, and from there it spread rapidly across Christendom. It is no coincidence that monasticism should have developed immediately after Constantine’s conversion, at the very time when the persecutions ceased and Christianity became fashionable. The monks with their austerities were martyrs in an age when martyrdom of blood no longer existed; they formed the counterbalance to an established Christendom. People in Byzantine society were in danger of forgetting that Byzantium was an image and symbol, not the reality; they ran the risk of identifying the kingdom of God with an earthly kingdom. The monks by their withdrawal from society into the desert fulfilled a prophetic and eschatological ministry in the life of the Church. They reminded Christians that the kingdom of God is not of this world.

Monasticism has taken three chief forms, all of which had appeared in Egypt by the year 350, and all of which are still to be found in the Orthodox Church today. There are first the hermits, ascetics leading the solitary life in huts or caves, and even in tombs, among the branches of trees, or on the tops of pillars. The great model of the eremitic life is the father of monasticism himself, St Antony of Egypt (25l-356). Secondly there is the community life, where monks dwell together under a common rule and in a regularly constituted monastery. Here the great pioneer was St Pachomius of Egypt (286-346), author of a rule later used by St Benedict in the west. Basil the Great, whose ascetic writings have exercised a formative influence on eastern monasticism, was a strong advocate of the community life, although he was probably influenced more by Syria than by the Pachomian houses that he visited. Giving a social emphasis to monasticism, he urged that religious houses should care for the sick and poor, maintaining hospitals and orphanages, and working directly for the benefit of society at large. But in general eastern monasticism has been far less concerned than western with active work; in Orthodoxy a monk’s primary task is the life of prayer, and it is through this that he serves others. It is not so much what a monk does that matters, as what he is. Finally there is a form of the monastic life intermediate between the first two, the semi-eremitic life, a ‘middle way’ where instead of a single highly organized community there is a loosely knit group of small settlements, each settlement containing perhaps between two and six members living together under the guidance of an elder. The great centres of the semi-eremitic life in Egypt were Nitria and Scetis, which by the end of the fourth century had produced many outstanding monks: Ammon the founder of Nitria, Macarius of Egypt and Macarius of Alexandria, Evagrius of Pontus, and Arsenius the Great. (This semi-eremitic system is found not only in the east but in the far west, in Celtic Christianity.) From its very beginnings the monastic life was seen, in both east and west, as a vocation for women as wel1 as men, and throughout the Byzantine world there were numerous communities of nuns.

Because of its monasteries, fourth-century Egypt was regarded as a second Holy Land, and travellers to Jerusalem felt their pilgrimage to be incomplete unless it included the ascetic houses of the Nile. In the fifth and sixth centuries leadership in the monastic movement shifted to Palestine, with St Euthymius the Great (died 473) and his disciple St Sabas (died 532). The monastery founded by St Sabas in the Jordan valley can claim an unbroken history to the present day; it was to this community that John of Damascus belonged. Almost as old is another important house with an unbroken history – the monastery of St Catherine at Mount Sinai, founded by the Emperor Justinian (reigned 527-565). With Palestine and Sinai in Arab hands, monastic pre-eminence in the Byzantine Empire passed in the ninth century to the monastery of Stoudios in Constantinople. St Theodore, who became Abbot here in 799, reactivated the community and revised its rule, attracting vast numbers of monks.

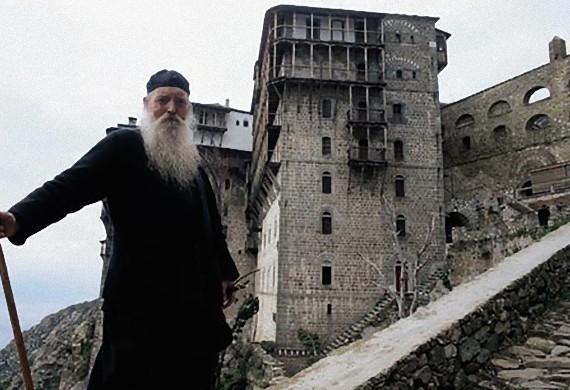

Since the tenth century the chief centre of Orthodox monasticism has been Athos, a rocky peninsula in North Greece jutting out into the Aegean and culminating at its tip in a peak 6,670 feet high. Known as ‘the Holy Mountain’, Athos contains twenty ‘ruling’ monasteries and a large number of smaller houses, as well as hermits’ cells; the whole peninsula is given up entirely to monastic settlements, and in the days of its greatest expansion it is said to have contained nearly forty thousand monks. The Great Lavra, the oldest of the twenty ruling monasteries, has by itself produced 26 Patriarchs and more than 144 bishops: this gives some idea of the importance of Athos in Orthodox history.

There are no ‘Orders’ in Orthodox monasticism. In the west a monk belongs to the Carthusian, the Cistercian, or some other Order; in the east he is simply a member of the one great fellowship which includes all monks and nuns, although of course he is attached to a particular monastic house. Western writers sometimes refer to Orthodox monks as ‘Basilian monks’ or ‘monks of the Basilian Order’, but this is not correct. St Basil is an important figure in Orthodox monasticism, but he founded no Order, and although two of his works are known as the Longer Rules and the Shorter Rules, these are in no sense comparable to the Rule of St Benedict.

A characteristic figure in Orthodox monasticism is the ‘elder’ or ‘old man’ (Greek geron; Russian starets, plural startsy). The elder is a monk of spiritual discernment and wisdom, whom others – either monks or people in the world – adopt as their guide and spiritual director. He is sometimes a priest, but often a lay monk; he receives no special ordination or appointment to the work of eldership, but is guided to it by the direct inspiration of the Spirit. A woman as well as a man may be called to this ministry, for Orthodoxy has its ‘spiritual mothers’ as well as its ‘spiritual fathers’. The elder sees in a concrete and practical way what the will of God is in relation to each person who comes to consult him: this is the elder’s special gift or charisma. The earliest and most celebrated of the monastic startsy was St Antony himself. The first part of his life, from eighteen to fifty-five, he spent in withdrawal and solitude; then, though still living in the desert, he abandoned this life of strict enclosure, and began to receive visitors. A group of disciples gathered round him, and besides these disciples there was a far larger circle of people who came, often from a long distance, to ask his advice; so great was the stream of visitors that, as Antony’s biographer Athanasius put it, he became a physician to all Egypt. Antony has had many successors, and in most of them the same outward pattern of events is found a withdrawal in order to return. A monk must first withdraw, and in silence must learn the truth about himself and God. Then, after this long and rigorous preparation in solitude, having gained the gifts of discernment which are required of an elder, he can open the door of his cell and admit the world from which formerly he fled.

Both in the capital and in other centres, the monastic movement continued to flourish as it was shaped during the early centuries of Christianity. The Constantinopolitan monastery of Studion was a community of over 1,000 monks, dedicated to liturgical prayer, obedience, and asceticism. They frequently opposed both government and ecclesiastical officialdom, defending fundamental Christian principles against political compromises. The Studite Rule (guidelines of monastic life) was adopted by daughter monasteries, particularly the famous Monastery of the Caves (Pecherskaya Lavra) in Kiev (in Russia). In 963 Emperor Nicephorus II Phocas offered his protection to St. Athanasius the Athonite, whose laura (large monastery) is still the centre of the monastic republic of Mt. Athos (under the protection of Greece). The writings of St. Symeon the New Theologian (949-1022), abbot of the monastery of St. Mamas in Constantinople, are a most remarkable example of Eastern Christian mysticism, and they exercised a decisive influence on later developments of Orthodox spirituality.

Historically, the most significant event was the missionary expansion of Byzantine Christianity throughout eastern Europe. In the 9th century, Bulgaria had become an Orthodox nation and under Tsar Symeon (893-927) had established its own autocephalous (administratively independent) patriarchate in Preslav. Under Tsar Samuel (976-1014) another autocephalous Bulgarian centre appeared in Ohrid. Thus, a Slavic-speaking daughter church of Byzantium dominated the Balkan Peninsula. It lost its political and ecclesiastical independence after the conquests of the Byzantine emperor Basil II (976-1025), but the seed of a Slavic Orthodoxy had been solidly planted. In 988 the Kievan prince Vladimir embraced Byzantine Orthodoxy and married a sister of Emperor Basil. After that time, Russia became an ecclesiastical province of the church of Byzantium, headed by a Greek or, less frequently, a Russian metropolitan appointed from Constantinople. This statute of dependence was not challenged by the Russians until 1448. During the entire period, Russia adopted and developed the spiritual, artistic, and social heritage of Byzantine civilization, which was received through intermediary Bulgarian translators.

Taken from a larger text, source:

http://orthodoxinfo.com/general/history3.aspx